Basic Structure of Hindi Poetry

Part 3- Rhythm in Mukt-Kavita (free verse)

Vani Murarka and Vinod Tewary

(Editors, Kaavyaalaya.org)

Email address: [email protected]

Preface

This is Part 3 of the article series on the basic structure of Hindi poetry. The whole article is in 4 parts as listed below:

Part 1: Structural units of a poem.

Part 2: Maatraa (मात्रा) or Meter of a Poem for Tukaant (तुकान्त), Chhanddobaddh

(छन्दोबद्ध) Poetry - i.e. poems that follow a clear rhyme and rhythm. These are perhaps the most important ingredients of the craft of poetry.

Part 2a: Software “Geet Gatiroop” to help in Maatraa counting

Part 3: (This part) Rhythm in Mukt-Kavita (free verse) based on Maatraa

and other structures.

Part 3a: Geet Gatiroop software for Mukt-Kavita

Part 4: Correspondence with Urdu poetry

1. Introduction

In this part we will describe the maatraa counting system with

examples from mukt and atukaant kavita and see how maatraa and

other structures of poetry enable the presence of rhythm in free

verse.

It is often assumed that free verse does not need to follow any

pattern or rules of rhythm. We respectfully differ with this

viewpoint.

Poetry must have a certain pattern that gives a sense of rhythm.

Rhythm gives to the reader a sense of flow, like a stream, which

carries her naturally to the next line and to the end of the poem.

This feeling of flow like a stream, is a characteristic attribute

of poetry. Rhythm is what enables the matter to directly impact

the readers’ subconscious, beyond the processing of the conscious

intellect. It facilitates recall.

In mukt-kavita the rhythm may be subtle but it must be there.

Usually the rhythm manifests in the form of periodicity of

maatraas. We will illustrate this point with some examples. A

little bit of maatraa count in Indian music is also included at

the beginning of this part in order to show the correspondence

between poetry and music.

2. Maatraa in Indian Music

Maatraa in poetry has almost exactly the same significance and the

same method of counting as in Indian music. We are therefore, giving

a brief description of maatraa in Indian music. First a disclaimer:

what has been written is a very amateurish understanding of the

basic maatraa structure of Indian music in the context of Hindi

poetry. Please consult a proper book to learn about maatraa structure

of Indian music.

In music maatraas are identified through tabla beats. Each beat

corresponds to a maatraa. There are differences in the allowed

structure of maatraas. In music there is the well-defined taal

(ताल) that a tabla player has to follow but the system of counting

is the same. One important difference between music and poetry

maatraas is that in music you can have half-maatraa. It means you

can telescope two notes into one tabla beat.

In Indian music there are taals like Kaharvaa, Daadraa, Teen-taal

etc (6, 12, and 16 maatraas). The whole song will have the

periodicity of these taals. The position of the 'sum' (सम) defines

the periodicity. Possibly there are no common taals with more than

16 maatraas (this may be wrong because of our almost zero knowledge

of music). Actually a human ear seems to be most sensitive to rhythm

of less than 20 - particularly 4. In western music, particularly

Jazz, the more common taal is the symmetric beat of 4, which also

seems to be more common in contemporary Hindi film songs.

Let us take an example of the following song which is usually sung

in Raag Malhaar with teen-taal (16 beats or maatraa). The maatraa

count is given below the words in each line:

| गरजत | बरसत | सावन | आयो | रे | |

| 1+1+1+1 | 1+1+1+1 | 2+1+1 | 2+1 | 1 | = 16 |

| आय | न | हमरे | बिछरे | बलमवा | |

| 2+1 | 1 | 1+1+2 | 1+1+1 | 1+1+1+2 | = 16 |

| सखि | का | करूं | हाय | रे | हाये | |

| 1+1 | 2 | 1+2 | 2+1 | 2 | 2+2 | = 16 |

Notice that in the first line (गरजत बरसत सावन आयो रे), the maatraa of यो and रे is one, not two. In music it would require the singer to pronounce them 'short'. Notice that it is the same in poetry.

Most likely, such a song would be sung in teen-taal. However, it is possible in music to reduce the maatraas by singing two sounds (letters or notes in music) in one beat or extending the maatraas by extending a sound. You would have noticed that singers will often speak some letters in rapid succession and extend some letters by adding aakaar (aaa..., or by adding sargam or taan as in tom-nomtaraanaa (तोम नोम तराना), or simply by using other sound fillers). These luxuries are not available in chhandobadhdh poetry but the techniques are used in mukt-kavita.

Now take another example of a different taal. Consider the following thumree: ( ठुमरी )

| बाट | चलत | नई | चुनरी | रंग | डारी | |

| 2+1 | 1+1+1 | 1+2 | 1+1+2 | 2+1 | 2+2 | = 20 |

| कैसो | है | अनारी | बनवारी | |

| 2+2 | 2 | 1+2+2 | 1+1+2+1 | = 16 |

| कैसो | है | अनारि | सखि | नन्द | का | लाला | |

| 2+2 | 2 | 1+2+2 | 1+2 | 1+1+1 | 1 | 2+2 | = 20 |

| बाट | चलत | छेड़त | मतवाला | |

| 2+1 | 1+1+1 | 2+1+1 | 1+1+2+2 | = 16 |

Notice that each line does not define periodicity but there is periodicity - the period being two lines. It is two lines that repeat. The total maatraa of two lines is 36 which is a multiple of 6 or 12. Thumrees are usually sung in Daadraa or Kaharwaa - taals of 12 and 6 beats. The point relevant to poetry is that you do not have to have periodicity of one line always. You can set the repetition pattern of your poem in terms of more than one line but your full poem must reflect that periodicity.

It is this more general periodicity that is used in mukt-kavita, which is described in the next sections. We use three different kinds of examples. First is the well-known Hindi movie song “Meraa Kuchh Saamaan” by Gulzar. Here we will see how the poem is primarily in rhythm, and how additions by the music composer (R D Burman) has further facilitated the maintenance of the rhythm. Second we shall see the example of a poem Jeevan Deep by Vinod Tewary that is mukt-kavita - however, further careful observation reveals that it is completely in meter. Third we shall see a small portion of Dharmveer Bharati’s Kanupriya which is a mukt-kavita khand-kaavya. Much greater liberties have been taken in Kanupriya, yet an underlying basic rhythm remains.

3. About the subsequent diagrams

Before we go further, a few words regarding the diagrams that have been used in the subsequent examples:

The diagrams have been generated using the Geet Gatiroop ( गीत गतिरूप ) software which was introduced in Part 2a of this article series.

We emphasize that the software is essentially a tool to help you to explore and refine the rhythmic aspects of poetry. It is not the final word regarding the correct count of maatraas or other aspects of poetry. It is vital that the reader obtains the knowledge of maatraas and rhythm in poetry. In fact, we must train our own internal ear towards the presence (and absence) of rhythm, beyond the need of the software or even the need to count maatraas manually. We can develop this by reading out aloud our own poems and those of others, and keeping awareness towards the rhythm. This enables a more natural emergence of poetry. Then, even small places where a misalignment occurs, become displeasing to our ear and we can spot it. In those places we can use the help of the software or of counting maatraas manually.

Now let us have a more detailed look at the presence of rhythm in mukt-kavita.

4a. Maatraas in Mukt-Kavita – Example of a movie song (by Gulzar)

It is simpler to start with an example of a song that has been professionally sung in a movie. Consider the following famous song/poem written by Gulzar for the film Ijaazat. It is rare that songs in Hindi movies be based on mukt-kavita. The majority are based on chhandobadh (metered) verse. This poem is an excellent example of mukt-kavita being transformed into a Hindi movie song. The story goes that when the music composer RD Burman saw the poem, his first remark was that it was like asking him to compose a tune for a piece from the Times of India newspaper!

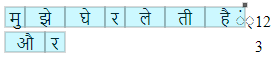

Here are a few lines from the song:

|

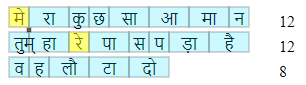

1: मेरा कुछ सा(आ)मान 2: तुम्हारे पास पड़ा है 3: वह लौटा दो Total of 12+12+8 = 32 |  |

|

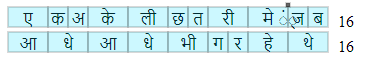

4: एक अकेली छतरी में जब 5: आधे आधे भीग रहे थे Total of 16+16 = 32 |  |

|

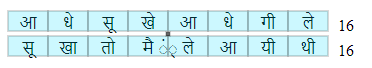

6: आधे सूखे आधे गीले 7: सूखा तो मैं ले आयी थी Total of 16+16 = 32 |  |

|

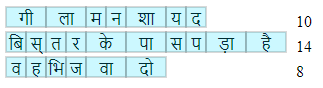

8: गीला मन शायद 9: बिस्तर के पास पड़ा है 10: वह भिजवा दो Total of Lines 10+14+8 = 32 |  |

|

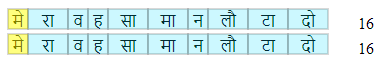

11: मेरा वह सामान लौटा दो 12: मेरा वह सामान लौटा दो Total of 16+16 = 32 |  |

As indicated in the numbers given below each group of lines, the periodicity is 32 maatraas. Lines 1,2, and 3 in fact serve as sthaayee. Notice that if you use only the word सामान in line 1, the first line will have only 10 maatraas which will make it 2 maatraas short. Now listen to the song carefully- the word saamaan is actually pronounced in the song with a very extended saa like saa-aa-maa-n. The music has to cover up the deficiency of two maatraas.

This maatraa count is just indicatory. As the poem is set to music, the same words and lines are sung differently in different parts of the song, which means that in those instances that alphabet is consuming more or less maatraas. This is a common feature of Indian music, where one word is sung in so many different ways.

In this example, note also the points at which a line is broken and the next line starts. They are not arbitrary. In a chhandobadhdh poem the line breaks are obvious because each line has the same length. In mukt-kavita generally the poet ensures that the end of a periodicity is also the end of a line, though there may be other line breaks before. If you read some well-known mukt-kavita, you will notice, the reader tends to automatically pause significantly at the end of certain lines. These are often not only the end of a logical content being said in the poem, but also the end of a periodicity. The reader’s mind subconsciously picks up the rhythm.

The poet certainly has much more liberty in mukt-kavita because the structure does not have to match every maatraa of every letter but a certain periodicity is essential. In poetry you have an additional liberty compared to a lyricist- you don't have to restrict yourself to taals in music that have to have 4,6,12, or 16 maatraas. You can have any periodicity but periodicity you must have.

The point of all the above is that a poem gets its charm from the rhythm that makes a poem singable (गेय). If a poem is not singable, then it is just a pretense of poetry. You do have liberties in the overall structure and, if necessary, manipulate the maatraas by short and long pronunciations but they should be within a reasonable framework. By reasonable, we mean that you cannot distort a word so much or add so much pause or lahraa that the word loses its meaning or the natural pronunciation is significantly distorted.

4b. Maatraas in Mukta-Kavita – example of a mukt-kavita poem

Now let us look at a Hindi poem “Jeevan Deep” that is free verse but on careful observation we find that it is totally in meter. It is written by one of us (Vinod Tewary). We suggest you first simply read the poem yourself (paying no attention to the diagram on the right) to see whether you naturally sense the rhythm and pauses or not.

|

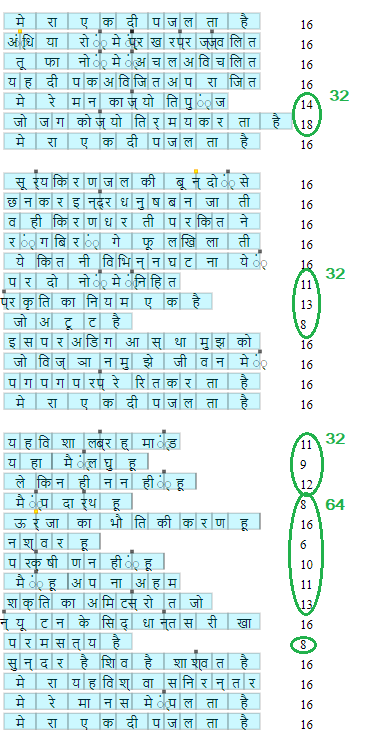

मेरा एक दीप जलता है। अंधियारों में प्रखर प्रज्ज्वलित, तूफानों में अचल, अविचलित, यह दीपक अविजित, अपराजित। मेरे मन का ज्योतिपुंज जो जग को ज्योतिर्मय करता है। मेरा एक दीप जलता है। सूर्य किरण जल की बून्दों से छन कर इन्द्रधनुष बन जाती, वही किरण धरती पर कितने रंग बिरंगे फूल खिलाती। ये कितनी विभिन्न घटनायें, पर दोनों में निहित प्रकृति का नियम एक है, जो अटूट है। इस पर अडिग आस्था मुझको जो विज्ञान मुझे जीवन में पग पग पर प्रेरित करता है। मेरा एक दीप जलता है। यह विशाल ब्रह्मांड यहाँ मैं लघु हूँ लेकिन हीन नहीं हूँ। मैं पदार्थ हूँ ऊर्जा का भौतिकीकरण हूँ। नश्वर हूँ, पर क्षीण नहीं हूँ। मैं हूँ अपना अहम शक्ति का अमिट स्रोत, जो न्यूटन के सिद्धान्त सरीखा परम सत्य है, सुन्दर है, शिव है शाश्वत है। मेरा यह विश्वास निरन्तर मेरे मानस में पलता है। मेरा एक दीप जलता है। |  |

The periodicity is of 16 maatraas. Some lines together form multiples of 16, such as 32 and 64, as indicated in the diagram. In one case, we have a line of 8 maatraas at the end of the poem, which is exactly half of 16. In many lines the poet has given line breaks as per his own unique expression, which often also corresponds to a comma. Yet, the lines together still maintain the periodicity of 16. This inherent rhythm is sensed naturally even upon reading.

This is an example of a mukt-kavita that totally follows the demands of periodicity despite being mukt (free).

4c. Maatraas in Mukt-Kavita – example of a khand-kaavya mukt-kavita

Now our final example is a piece from Dharmveer Bharti's Kanupriya. It is a beautiful long poem with several chapters, kind-of like a novella in free verse. Some chapters of Kanupriya are available on Kaavyaalaya.org. Our analysis is of a piece from the chapter Aamra Baur Kaa Geet.

For the purpose of analysis of rhythm, line breaks may not be the same as in the poem on Kaavyaalaya. The line breaks are given here in order to demonstrate the maatraa count and its periodicity.

First, the lines, just like that, for your reading and imbibing pleasure:

|

भय, संशय, गोपन, उदासी ये सभी ढीठ, चंचल, सरचढ़ी सहेलियों की तरह मुझे घेर लेती हैं, और मैं कितना चाह कर भी तुम्हारे पास ठीक उसी समय नहीं पहुँच पाती जब आम्र मंजरियों के नीचे अपनी बाँसुरी में मेरा नाम भरकर तुम बुलाते हो! उस दिन तुम उस बौर लदे आम की झुकी डालियों से टिके कितनी देर मुझे वंशी से टेरते रहे ढलते सूरज की उदास काँपती किरणें तुम्हारे माथे मे मोरपंखों से बेबस विदा माँगने लगीं - मैं नहीं आयी |

Now the analysis -

|

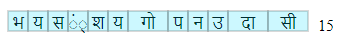

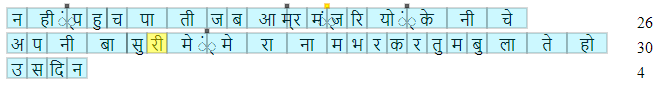

भय, संशय, गोपन, उदासी Total: 15 |  |

|

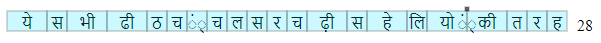

ये सभी ढीठ, चंचल, सरचढ़ी सहेलियों की तरह Total: 28 (2 short of 30) |  |

|

मुझे घेर लेती हैं और Total: 15 |  |

|

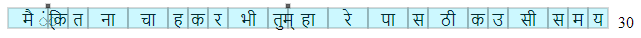

मैं कितना चाह कर भी तुम्हारे पास ठीक उसी समय Total: 30 |  |

|

नहीं पहुँच पाती जब आम्र मंजरियों के नीचे अपनी बाँसुरी में मेरा नाम भरकर तुम बुलाते हो! उस दिन Total: (26+30+4) = 60 (15*4) |  |

|

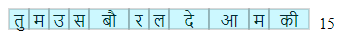

तुम उस बौर लदे आम की Total: 15 |  |

|

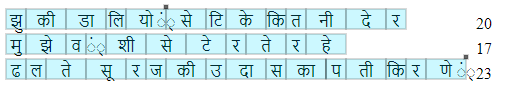

झुकी डालियों से टिके कितनी देर मुझे वंशी से टेरते रहे ढलते सूरज की उदास काँपती किरणें Total: (20+17+23) = 60 (15*4) |  |

|

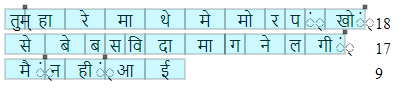

तुम्हारे माथे मे मोरपंखों से बेबस विदा माँगने लगीं - मैं नहीं आई Total: (18+17+9) = 44 (1 short of 45) |  |

The periodicity of the above poem is clearly 15 maatraa. Line 2 is two maatraa short which can be compensated by elongating the words or by pauses. Similarly the last group of lines is one maatraa short. Some discrepancies in a long poem like this are not serious because they can be compensated, but the overall periodicity / rhythm must be there.

In mukt-kavita there is much greater flexibility in where the line breaks are inserted. However, the pauses at significant junctures that define the inherent periodicity must be conveyed. This is done mostly by line breaks and paragraph breaks. Other punctuations may also play a role in this, such as a dash, ellipsis or others.

5. Challenge of Free Verse

There is significantly greater flexibility available to the poet regarding adherence to a meter in mukt-kavita. We saw this progressively in the examples above. This generally gives the impression that writing free verse is easier. However, in one sense, this is not so. As we have repeatedly said, the onus still lies on the poet to provide the rhythm. This is a demand of poetry, and an intrinsic need for the reader of poem. Free verse is in fact tougher for a reader to read. Hence, in a way, it is more challenging for a poet to write free verse and still make sure that it does not degenerate into a pretense of poetry.

In the case of metered poetry, once the poet imbibes the rhythm of the meter into her being (much like the repetitive sound of a train that passengers experience), that rhythm actually serves as a handle for the poet that she can always hold. The thoughts that emerge in the poet’s mind, emerge largely within the construct of the chosen meter and rhythm. This can be very comforting and reassuring for the poet. This vessel that can hold the poet’s flow, is not available so explicitly in the case of free-verse. This can easily make a poet feel at a loss at times – and the reader too!

Apart from a general adherence to metric periodicity, poets also use other structures to give the semblance of rhythm. These are, the presence of rhyming words and repetition of phrases. While they may not occur at well defined places as in the case of tukaant (rhyming) verse, the presence of some lines that match by rhyme to some near-by lines, gives a sense of assurance and rhythm to the reader. While rhyme is considered a form of alankaar (decoration) in the craft of poetry, it also plays the role of bringing in rhythm. Meter brings rhythm into poetry via the temporal dimension. Rhyme brings rhythm into poetry via the phonetic dimension.

Similarly, repetition of phrases can give a sense of rhythm and assurance to the reader in free verse. For example, Amra Baur Kaa Geet ends with “main naheen aayee” in many of the verses/chhand. This adds to the charm of this particular chapter of Kanupriya.

These aspects, the importance of rhythm, becomes more crucial when the free verse is longer than say about 5-6 lines.

6. Conclusion

A poem must be singable or hummable (गेय) even if it is mukt-kavita. In order to be geya, a poem must have rhythm, even if not tuk (rhyme). Mukt-kavita gives you some liberty from the constraints of a rigid structure of poetry but it still must have an inherent rhythm. It is not simply that you write prose and break the lines at arbitrary points.

Finally, the good news: if you feel intimidated by the thought of doing all the arithmetic associated with the maatraa count, please relax. You don't have to count the maatraas. Just try to hum ( गुनगुनाइए) what you write in a uniform rhythm (without cheating yourself). If you can hum it without breaks, then your poem is fine. You don't need to count maatraas but it might be instructive. If you find the rhythm breaking somewhere, count the maatraas at that point. It will give you an indication of what words need to be changed and what are the possibilities. A computer can count the maatraas; it cannot write poetry or create music. That needs a human being - at least for now.

Next, Part 3a: Geet Gatiroop software for Mukt-Kavita

After that, in Part 4, we will talk about the structure of Urdu poetry.

18 April 2014

Modified on 19 December 2019. Images were updated to reflect the latest output from Geet Gatiroop.